Your Local Broker, Internationally

Berthon UK

(Lymington, Hampshire - UK)

Sue Grant

sue.grant@berthon.co.uk

0044 (0)1590 679 222

Berthon Scandinavia

(Henån, Sweden)

Magnus Kullberg

magnus.kullberg@berthonscandinavia.se

0046 304 694 000

Berthon Spain

(Palma de Mallorca, Spain)

Simon Turner

simon.turner@berthoninternational.com

0034 639 701 234

Berthon USA

(Rhode Island, USA)

Jennifer Stewart

jennifer.stewart@berthonusa.com

001 401 846 8404

Nice Ice for Samoa 47’ DESTINY

By Andrew Fennymore-White, Photography © Andrew Fennymore-White

My current worries about ice are whether there are sufficient cubes for a Margarita for Janice and myself but after 8 years of cruising in the Arctic, West to Baffin Island and East to Hammerfest, that is a pleasant distraction. We are just coming to the end of our second winter season spent in the Caribbean.

Which do we prefer?

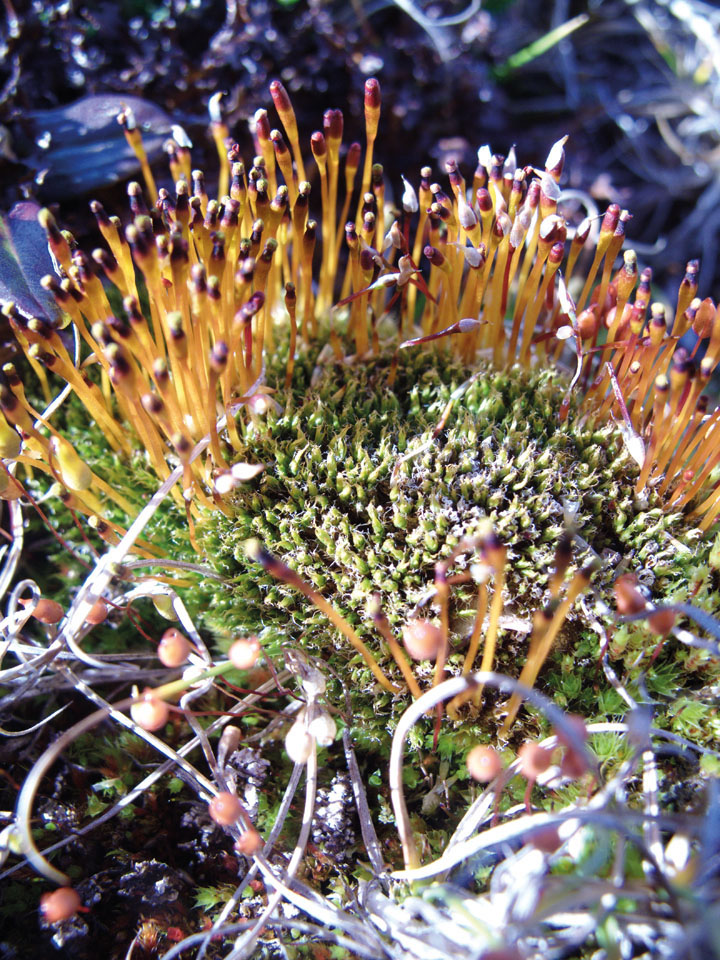

Without doubt the Arctic. In the purity of the air, mirages shimmer, reflected by cold air, judging distance becomes a guessing game. From early spring light rapidly increases until life seems to be running at double speed, plants and creatures all frantically reproducing before the long night cycle begins again. Nothing seems to sleep. The landscapes can be incredibly harsh but beautiful on a micro scale; orchids, saxifrage, lichens, dense mosses. There is an abundance of wildlife not found in the tropics; whales, seals, bears and birds to name a few that are incredibly curious the more remote you travel. I once had a very young reindeer run around me all loose fluffy skin and knobbly kneed, bleating and nudging me. I suspect it had never had a two legged playmate before.

But it’s the frozen side of the Arctic where the real magic lies. The snow, with its individual flakes silently falling on deck, and the ice. Ice in all its forms. An anchorage that has frozen overnight with a thin Nilas, a crust a centimetre thick but enough to silence the water. A chunk of glacial ice glowing from within, a water eroded lump, a perfect turtle sculpture. A flower encrusted, a gleaming cathedral sliding past. Of all the elements, it is the ice that grabs the attention and demands the most respect.

So how do you experience this wilderness?

Most cruisers will not have the space to have a pilot or professional Captain on board but are sole minded enough to want to be independent anyway, which is why they are cruisers in the first instance. I think the first item must be a strong vessel, robust enough for inevitable unforecast heavy weather but still able to sail in light airs. Arctic sailing is fickle; we estimate around 40% motoring. A powerful engine that will get you safely into an anchorage should not be underestimated, with lots of fuel, 1,000 nm range at a minimum. A comfortable place to relax while gale bound at anchor with heating running smoothly should be high on your list. Independence from gas is another great asset. Greenland only sells huge 30kg bottles and those are non-refundable.

Next comes the confidence in your own ability as a crew to understand the environment and your vessel. The ability to overcome the inevitable breakdowns which not only means having the spares and tools organised on board, but the knowledge to use and adapt them for the current problem and a space to work. Being a great racer or captain of industry will not help you, but years of tinkering and fixing broken stuff will. A ‘never give up’ mentality will go a long way, duct tape and zip ties not so far. You and your crew are the only help in many Arctic locations. East Greenland in 2017, we failed to see a single vessel in the 600nm stretch from Tasillaq to Cape Farvel. Likewise in 2016 we were off all electronic charts for 3 weeks in Nordaustlandet, Svalbard, not a sole seen.

Modern satellite computers have meant getting a good forecast is straightforward now and that goes for reasonable ice forecasts but a chart showing 3/10 ice cover doesn’t mean the ice is evenly spreadout. It’s often blown or swept by currents into thick bands. Local currents might fill a bay entirely on a rising tide and empty it on the ebb. Confidence in ice comes with experience but the rules are fairly straight forward. Have a look out in the mast if possible; don’t go into a tight cul de sac; don’t enter ice fields of any size if there is a heavy sea running; don’t sail too close to large bergy bits – if there is ice 20m above the water, when it rotates over or breaks in two that might be 100 meters thrusting up out of the deep with a large wave preceding it. Classic shots of your yacht framed in an ice arch look nice but you need the tricks of a long lens to pull it off.

Be careful where you anchor as it’s easy to get blocked in and find it impossible to manoeuvre or retrieve your anchor. We had a close shave with DESTINY in the spring of 2018 when at anchor. During a cold front induced wind shift, acres of fast ice broke free from the shore and charged down on us. We only had a minute to dump our starboard anchor before the ice would carry DESTINY onto the new leeshore, just metres astern. The warp securing the bitter end of the chain was just long enough to allow it to be cut on deck and we motored into free water with seconds to spare. Gratefully we dropped our port anchor and went to bed, happy to have a reliable anchor down and thanking our lucky stars that one of us had seen the ice breaking free as we cleaned our teeth. The following day we had much fun successfully dredging for our lost anchor.

Radar also has its use to confirm the charts accuracy. For instance the entrance to Tasillaq, East Greenland has a significant offset error. We came in with thick fog after 12 hours of heavy ice strewn water to then have to radar pilot through the entrance. Not being able to rely on the chart plotter was not appreciated, but a lookout on the bow and a slow patient approach was way preferable to staying out in the ice motoring.

Forward looking sonar is also a great asset. I have always used EchoPilot and I think it has earned its place aboard. A forward sonar will alert you to an uncharted rock 2 or 3 boat lengths away in calm water and there are a lot of those in the Arctic. It allows a good sweep of an anchorage, giving confidence during wind shifts or nosing into tight passages. Having a lift keel is a fantastic advantage. If you can anchor in shallow water you know most larger pieces of ice will ground long before reaching you, equally using your keel as a joker card pays dividends. We try to never anchor keel full up, but always keep at least 0.5m in hand in case we get grounded.

A personal rule is always wear a full immersion suit while in the tender and, if we are both going ashore, to be equipped should your tender be lost to a curious bear or walrus or simply blown away. Radio, sat phone, flares, food, shelter and a rifle of course go a long way for your survival if the unexpected happens.

Plan your first Arctic trip mid-summer when the daylight is continuous, the ice at a minimum, the weather warm and pleasant. East Greenland is quite seriously remote, West Greenland much more approachable but a long sail from the UK. Svalbard with an over winter in Norway is a good introduction and there are plenty of other cruisers with a good but bureaucratic infrastructure.

Read Another Article

Download the Berthon Book 2023-2024 XIX (21.3MB)